Introduction to Scenarios

Arden Brummell and Greg MacGillivray

Managing Directors,

Scenarios to Strategy Inc.

Few companies today would say they are happy with the way they plan for an increasingly fluid and turbulent business environment. Traditional planning was based on forecasts ...

Forecasts are not always wrong; more often than not, they can be reasonably accurate. And that is what makes them so dangerous. They are usually constructed on the assumption that tomorrow's world will be much like today's...

(The problem is) in anticipating major shifts in the business environment ... the way to solve this problem is not to look for better forecasts ... the right forecast. The future is no longer stable; it has become a moving target...

The better approach, I believe, is to accept uncertainty, try to understand it, and make it part of your reasoning. Uncertainty today is not just an occasional, temporary deviation from a reasonable predictability; it is a basic structural feature of the business environment.

Pierre Wack

"Scenarios: Uncharted Waters Ahead"

WHAT ARE SCENARIOS?

Scenarios are alternative descriptions of the business environment. They are stories, images or maps of the future. They are internally consistent stories describing paths from the present to a future time horizon. Good scenarios are rooted in the past and in the present. They provide an interpretation of past and present events projected into the future. The key focus of scenarios is uncertainty. The objective is to identify the major uncertainties affecting the strategic decisions facing a business or the policy issues facing governments. Scenarios help chart the waters ahead so that the consequences of today’s decisions can be played out, evaluated and tested against the uncertainty of the future.

That is the logic. The reality is more subtle. Again quoting from Pierre Wack:

"Scenarios help managers structure uncertainty when (1) they are based on a sound analysis of reality, and (2) they change the decision makers' assumptions about how the world works ... their mental model of reality."

The objective is to expand the envelope of our thinking and to expand the limits of our mental maps of the future. In that respect, the process of scenario development is as important as the final product.

WHY SCENARIOS?

As Pierre Wack indicated in the opening quote, scenarios are an approach to thinking about the future by focusing on key uncertainties facing managers in making strategic decisions. Scenarios are a means to an end and not the end itself. Developing scenarios involves taking a wealth of information about the past and present, identifying patterns, and structuring coherent stories about the future. An organization can then use the scenarios to think through their strategic options and decisions.

Scenarios are most useful when the external environment is complex and uncertain and key decisions involve major investments or have long term consequences. Complex environments typically involve non-quantifiable factors, where structural change is a component of the uncertainty and where systems have complicated feedback loops.

Increasingly, systems thinking, which recognizes how behaviour within systems can lead to unanticipated feedback, is an important part of scenario thinking. For situations in which most of the variables are known and quantifiable, scenarios are not very useful. Similarly, for decisions with relatively short term outcomes, scenarios are usually not appropriate.

THE VALUE OF SCENARIOS AND SCENARIO PLANNING

The value of scenarios as a product:

_ Builds understanding of the broader business environment

_ Embraces and structures uncertainty

_ Creates a vocabulary about the future and identifies alternative futures

_ Makes key assumptions explicit and surfaces hidden risks

_ Provides a context for developing and testing strategic options or policies

The value of scenario planning as process:

_ Provides a vehicle for increased communication and shared learning

_ Builds the strategic capacity of participants

_ Provides a forum for sharing views from all parts of a company

_ Allows unconventional views and new ideas to surface

_ Builds organizational alignment, commitment and performance

Scenarios provide insight. While the process is designed to produce scenarios, the learning that occurs through the scenario development process may actually be more valuable than the specific scenarios developed.

SCENARIO CHARACTERISTICS

Scenarios may be very broad or very focused. They may emphasize long term trends or the dynamics of key variables over time. They may explore key themes or ranges. There are 5 common characteristics of scenarios worth noting.

1) Multiple Views: Scenarios always involve more than one view of the future. That is their explicit objective. A single view is a forecast.

2) Qualitative Change: Scenarios are most appropriate when dealing with complex, highly uncertain situations in which qualitative, non-quantifiable forces are at work. (e.g., social values, technology, regulations, etc.).

3) Objective: Scenarios describe what could happen, not what we want to happen. Objectivity requires that scenarios be internally consistent and feasible. If scenarios are viewed as impossible or not feasible, they are rejected. The challenge is to broaden thinking without becoming unbelievable.

4) Open-Ended: Scenarios are stories. They do not provide precise details. Challenging and engaging scenarios allow the reader to add details which help bring the scenarios alive.

5) Focused and Relevant: Scenarios must be relevant to the situation at hand. They must focus on the driving forces and the critical uncertainties relevant to strategic decisions under consideration.

HOW ARE SCENARIOS DEVELOPED?

In his book, Art of the Long View, Peter Schwartz observed that scenarios are about perceiving futures in the present. The idea is that the seeds of the future are present today, if only we could interpret them. We apply this simple idea in developing scenarios. Our challenge is to identify the “seeds”, interpret their significance and project their implications into the future.

An example is useful. Consider the stock market crash of 1987. This was recognized at the time as a major event or "seed". What did it mean? What was its significance? At least two interpretations were debated. One interpretation, primarily from Wall Street analysts, argued that the crash was a technical correction. The market had been rising for a long time and an adjustment from profit-taking was inevitable. It required no major response by governments or investors. A second interpretation, primarily from economists, argued that the stock market crash signaled a fragile and unsustainable international financial system. The system had been built on a mountain of debt and was a financial "house of cards.” Massive and immediate intervention by governments to prevent a collapse of the international financial system was required.

Notice how different interpretations of the same event created different future expectations (projected future) and would have led to different decisions by key actors. In the end, governments did act collectively by increasing the liquidity in the system and the international financial system proved to be remarkably resilient. Their response was less than the economists and more than the stock market analysts had advocated.

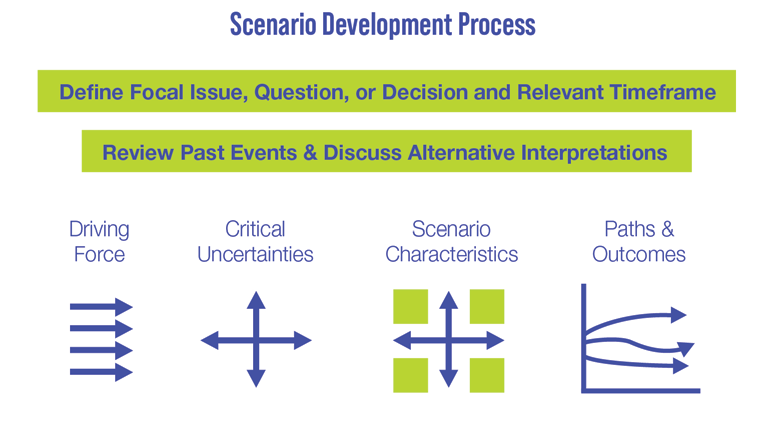

THE SCENARIO PLANNING PROCESS

S2S has developed a structured approach to building scenarios. As shown in the figure below, the scenario planning process involves the following steps:

1) Clarifying the focus of the scenarios (a focal question)

2) Examining past changes to identify ongoing trends and forces

3) Identifying future changes and the forces driving those changes

4) Identifying the critical uncertainties which could lead to distinctly different futures

5) Creating a logical framework based on the critical uncertainties

6) Fleshing out the major characteristics and developing stories for each scenario

7) Identifying the major implications of the scenarios on the organization

Forecasts are not always wrong; more often than not, they can be reasonably accurate. And that is what makes them so dangerous. They are usually constructed on the assumption that tomorrow's world will be much like today's...

(The problem is) in anticipating major shifts in the business environment ... the way to solve this problem is not to look for better forecasts ... the right forecast. The future is no longer stable; it has become a moving target...

The better approach, I believe, is to accept uncertainty, try to understand it, and make it part of your reasoning. Uncertainty today is not just an occasional, temporary deviation from a reasonable predictability; it is a basic structural feature of the business environment.

Pierre Wack

"Scenarios: Uncharted Waters Ahead"

WHAT ARE SCENARIOS?

Scenarios are alternative descriptions of the business environment. They are stories, images or maps of the future. They are internally consistent stories describing paths from the present to a future time horizon. Good scenarios are rooted in the past and in the present. They provide an interpretation of past and present events projected into the future. The key focus of scenarios is uncertainty. The objective is to identify the major uncertainties affecting the strategic decisions facing a business or the policy issues facing governments. Scenarios help chart the waters ahead so that the consequences of today’s decisions can be played out, evaluated and tested against the uncertainty of the future.

That is the logic. The reality is more subtle. Again quoting from Pierre Wack:

"Scenarios help managers structure uncertainty when (1) they are based on a sound analysis of reality, and (2) they change the decision makers' assumptions about how the world works ... their mental model of reality."

The objective is to expand the envelope of our thinking and to expand the limits of our mental maps of the future. In that respect, the process of scenario development is as important as the final product.

WHY SCENARIOS?

As Pierre Wack indicated in the opening quote, scenarios are an approach to thinking about the future by focusing on key uncertainties facing managers in making strategic decisions. Scenarios are a means to an end and not the end itself. Developing scenarios involves taking a wealth of information about the past and present, identifying patterns, and structuring coherent stories about the future. An organization can then use the scenarios to think through their strategic options and decisions.

Scenarios are most useful when the external environment is complex and uncertain and key decisions involve major investments or have long term consequences. Complex environments typically involve non-quantifiable factors, where structural change is a component of the uncertainty and where systems have complicated feedback loops.

Increasingly, systems thinking, which recognizes how behaviour within systems can lead to unanticipated feedback, is an important part of scenario thinking. For situations in which most of the variables are known and quantifiable, scenarios are not very useful. Similarly, for decisions with relatively short term outcomes, scenarios are usually not appropriate.

THE VALUE OF SCENARIOS AND SCENARIO PLANNING

The value of scenarios as a product:

_ Builds understanding of the broader business environment

_ Embraces and structures uncertainty

_ Creates a vocabulary about the future and identifies alternative futures

_ Makes key assumptions explicit and surfaces hidden risks

_ Provides a context for developing and testing strategic options or policies

The value of scenario planning as process:

_ Provides a vehicle for increased communication and shared learning

_ Builds the strategic capacity of participants

_ Provides a forum for sharing views from all parts of a company

_ Allows unconventional views and new ideas to surface

_ Builds organizational alignment, commitment and performance

Scenarios provide insight. While the process is designed to produce scenarios, the learning that occurs through the scenario development process may actually be more valuable than the specific scenarios developed.

SCENARIO CHARACTERISTICS

Scenarios may be very broad or very focused. They may emphasize long term trends or the dynamics of key variables over time. They may explore key themes or ranges. There are 5 common characteristics of scenarios worth noting.

1) Multiple Views: Scenarios always involve more than one view of the future. That is their explicit objective. A single view is a forecast.

2) Qualitative Change: Scenarios are most appropriate when dealing with complex, highly uncertain situations in which qualitative, non-quantifiable forces are at work. (e.g., social values, technology, regulations, etc.).

3) Objective: Scenarios describe what could happen, not what we want to happen. Objectivity requires that scenarios be internally consistent and feasible. If scenarios are viewed as impossible or not feasible, they are rejected. The challenge is to broaden thinking without becoming unbelievable.

4) Open-Ended: Scenarios are stories. They do not provide precise details. Challenging and engaging scenarios allow the reader to add details which help bring the scenarios alive.

5) Focused and Relevant: Scenarios must be relevant to the situation at hand. They must focus on the driving forces and the critical uncertainties relevant to strategic decisions under consideration.

HOW ARE SCENARIOS DEVELOPED?

In his book, Art of the Long View, Peter Schwartz observed that scenarios are about perceiving futures in the present. The idea is that the seeds of the future are present today, if only we could interpret them. We apply this simple idea in developing scenarios. Our challenge is to identify the “seeds”, interpret their significance and project their implications into the future.

An example is useful. Consider the stock market crash of 1987. This was recognized at the time as a major event or "seed". What did it mean? What was its significance? At least two interpretations were debated. One interpretation, primarily from Wall Street analysts, argued that the crash was a technical correction. The market had been rising for a long time and an adjustment from profit-taking was inevitable. It required no major response by governments or investors. A second interpretation, primarily from economists, argued that the stock market crash signaled a fragile and unsustainable international financial system. The system had been built on a mountain of debt and was a financial "house of cards.” Massive and immediate intervention by governments to prevent a collapse of the international financial system was required.

Notice how different interpretations of the same event created different future expectations (projected future) and would have led to different decisions by key actors. In the end, governments did act collectively by increasing the liquidity in the system and the international financial system proved to be remarkably resilient. Their response was less than the economists and more than the stock market analysts had advocated.

THE SCENARIO PLANNING PROCESS

S2S has developed a structured approach to building scenarios. As shown in the figure below, the scenario planning process involves the following steps:

1) Clarifying the focus of the scenarios (a focal question)

2) Examining past changes to identify ongoing trends and forces

3) Identifying future changes and the forces driving those changes

4) Identifying the critical uncertainties which could lead to distinctly different futures

5) Creating a logical framework based on the critical uncertainties

6) Fleshing out the major characteristics and developing stories for each scenario

7) Identifying the major implications of the scenarios on the organization

The scenarios developed provide a context for examining the risks and opportunities associated with different strategic choices or policy options. They become a tool to examine the future of consequences of decisions being made today.

"The evolutionary race goes to the adaptable, not to the well adapted,

to those who can learn, not to those who know."

Kenneth Boulding

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD SCENARIOS

Since scenarios are not predictions, how do you evaluate whether they are good or bad? The criteria are largely subjective but relate to the characteristics and objectives of scenarios.

Good scenarios are:

1) Plausible: Are the scenarios believable?

2) Grounded: Are the scenarios linked to events in the past and present?

3) Challenging: Do the scenarios challenge our thinking? Do they expand our mental maps?

4) Relevant: Do the scenarios cast light on the important strategic issues facing our organization?

5) Internally consistent: Are there any contradictions in the scenario logic or scenario outcomes?

And the greatest distinguishing characteristic of a good scenario is asking:

"The only relevant discussions about the future are those where

we succeed in shifting the question from whether something will

happen to what would we do if it did happen"

Arie de Geus

Former Coordinator, Group Planning

Shell International Petroleum Company

"The evolutionary race goes to the adaptable, not to the well adapted,

to those who can learn, not to those who know."

Kenneth Boulding

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD SCENARIOS

Since scenarios are not predictions, how do you evaluate whether they are good or bad? The criteria are largely subjective but relate to the characteristics and objectives of scenarios.

Good scenarios are:

1) Plausible: Are the scenarios believable?

2) Grounded: Are the scenarios linked to events in the past and present?

3) Challenging: Do the scenarios challenge our thinking? Do they expand our mental maps?

4) Relevant: Do the scenarios cast light on the important strategic issues facing our organization?

5) Internally consistent: Are there any contradictions in the scenario logic or scenario outcomes?

And the greatest distinguishing characteristic of a good scenario is asking:

"The only relevant discussions about the future are those where

we succeed in shifting the question from whether something will

happen to what would we do if it did happen"

Arie de Geus

Former Coordinator, Group Planning

Shell International Petroleum Company