Evolution of scenarios

In the late 1960s, the planning group within Royal Dutch Shell did an analysis of the

global oil market to the year 2000. No one believed it. Pierre Wack, head of

Group Planning, decided there had to be another way of developing perspectives

on the future. After a global search (nice to have the budget) he came back with an

answer: scenarios.

The first Shell scenario work in the early 1970s focused on the rising power

of national governments, prospects of nationalization, and potential restrictions on

supply. Coupled with that was the steady rise in oil demand. For decades, oil demand

had been increasing at 6 percent to 7 percent annually. This was the norm; this was

the assumption. But what did it really mean?

A critical question in developing any outlook of the future is to overcome the

inertia of the present. How can we get decision makers to open their minds to

change? How do we get them to ask the question, what happens if our current

assumptions are wrong? Wack created a simple scenario. He projected the growth in

demand from 1970 to 1980 on the basis of existing assumptions of future growth.

Then he presented the results in a distinct way. If current demand continued to grow

at existing rates, then by 1980 the global oil industry would need to open a new

refinery every day of the year.

The impact was profound. The Committee of Managing Directors at Royal

Dutch Shell immediately realized that was not going to happen. Suddenly, they were

open to new ideas. Something had to give. Price, which had hovered near $3 per

barrel for years, would be the likely candidate. And, as the results of the oil embargo

in 1973 confirmed, price was indeed the item that would give.

There are many lessons from this simple story. Most important is that the value

of scenario thinking is to open minds, to create understanding of a broader range

of possible future outcomes, and to enhance the ability to adapt. Opening minds

increases the ability to adapt to change. This thinking is credited with Shell’s response

to the 1973 oil embargo. Shell did not predict the details of the embargo, but the

scenario work is believed to have opened perspectives such that Shell’s response

was more measured and forward looking than many of the other oil majors, and

ultimately, a key to Shell’s expansion from the smallest to one of the largest of the

Seven Sisters.1

Other insights were to follow. The importance of scenarios as a vehicle for shaping

mental models was not fully understood for some years and was probably not articulated

until the late 1970s. A second learning was the realization that scenarios focused

on uncertainties. In the late 1980s, Kees van der Heijden would clarify the concept

of irreducible uncertainties—variables in which the range of uncertainty cannot be

reduced by further analysis. Scenarios were not intended to predict the future but

to understand and embrace uncertainty and the range of future possible outcomes.

Strategically, a range of future outcomes allows the consequences of major decisions

to be analyzed across the different scenarios. This was the key connection between

scenarios and strategy. Scenarios provided a framework for evaluating the potential

consequences of a given strategy across scenarios to test the robustness of the strategy.

Much more on this later. But suffice to note that this was the exact opposite of forecasting,

which was designed to reduce uncertainty to the most likely outcome. As the

refinery story suggests, putting all your eggs in one basket, or forecast, is dangerous.

The next major step in scenario planning was the methodology developed at

Global Business Network (GNB), led by Jay Ogilvy and Peter Schwarz. Scenario

development in Shell was not a well-documented process. Scenarios were developed

by a small number in Group Planning, and individuals learned the approach

more or less by osmosis. GBN was the first to develop and publicize a structured

methodology to develop scenarios. Peter Schwarz’s 1991 book, The Art of the Long

View, outlined an approach to developing scenarios focused on identifying critical

uncertainties. Moreover, the process involved working through a series of steps in a

workshop setting. The central logic that scenarios were focused on identifying and

understanding uncertainties was crystallized by the methodology created by GBN.

The last major step in the evolution of scenario planning was connecting scenarios

to strategy. This is less well defined. The first major step in connecting scenarios

to decision-making involved two ideas developed by Kees van der Heijden.

One was the seven questions; the other was the management implications workshop.

The role of the seven questions was to elicit input from senior managers who did

not participate directly in developing the scenarios. The questions provided useful

information on management’s perspectives, created a direct link to management, and

built management support for the scenarios.

The other was the management implications workshop, first used with the 1989 Shell

scenarios, engaged management teams by asking the simple question: What are the

implications of the scenarios for your business? It evoked great conversation, embedded

the scenarios in the minds of senior managers, and created a mental mindset open to

new ideas and a willingness to act.

While this was a first step in creating strategic thinking, the process was not well

structured. In working first with Lee van Horn at Palomar Consulting and then

with Greg MacGillivray at Scenarios to Strategy, a structured process to link the

creative work of scenarios with the more focused work of strategy development

and implementation was developed. The process identifies the implications of the

scenarios, strategic thrusts, or focus areas, for the organization, goals, strategies, and

actions. The analysis linking the scenarios to strategy can vary depending on the level

of senior management involved, the objectives of the project, and the expected role

of the facilitators. Describing a process to link scenarios to strategy is a major aspect

of this work.

global oil market to the year 2000. No one believed it. Pierre Wack, head of

Group Planning, decided there had to be another way of developing perspectives

on the future. After a global search (nice to have the budget) he came back with an

answer: scenarios.

The first Shell scenario work in the early 1970s focused on the rising power

of national governments, prospects of nationalization, and potential restrictions on

supply. Coupled with that was the steady rise in oil demand. For decades, oil demand

had been increasing at 6 percent to 7 percent annually. This was the norm; this was

the assumption. But what did it really mean?

A critical question in developing any outlook of the future is to overcome the

inertia of the present. How can we get decision makers to open their minds to

change? How do we get them to ask the question, what happens if our current

assumptions are wrong? Wack created a simple scenario. He projected the growth in

demand from 1970 to 1980 on the basis of existing assumptions of future growth.

Then he presented the results in a distinct way. If current demand continued to grow

at existing rates, then by 1980 the global oil industry would need to open a new

refinery every day of the year.

The impact was profound. The Committee of Managing Directors at Royal

Dutch Shell immediately realized that was not going to happen. Suddenly, they were

open to new ideas. Something had to give. Price, which had hovered near $3 per

barrel for years, would be the likely candidate. And, as the results of the oil embargo

in 1973 confirmed, price was indeed the item that would give.

There are many lessons from this simple story. Most important is that the value

of scenario thinking is to open minds, to create understanding of a broader range

of possible future outcomes, and to enhance the ability to adapt. Opening minds

increases the ability to adapt to change. This thinking is credited with Shell’s response

to the 1973 oil embargo. Shell did not predict the details of the embargo, but the

scenario work is believed to have opened perspectives such that Shell’s response

was more measured and forward looking than many of the other oil majors, and

ultimately, a key to Shell’s expansion from the smallest to one of the largest of the

Seven Sisters.1

Other insights were to follow. The importance of scenarios as a vehicle for shaping

mental models was not fully understood for some years and was probably not articulated

until the late 1970s. A second learning was the realization that scenarios focused

on uncertainties. In the late 1980s, Kees van der Heijden would clarify the concept

of irreducible uncertainties—variables in which the range of uncertainty cannot be

reduced by further analysis. Scenarios were not intended to predict the future but

to understand and embrace uncertainty and the range of future possible outcomes.

Strategically, a range of future outcomes allows the consequences of major decisions

to be analyzed across the different scenarios. This was the key connection between

scenarios and strategy. Scenarios provided a framework for evaluating the potential

consequences of a given strategy across scenarios to test the robustness of the strategy.

Much more on this later. But suffice to note that this was the exact opposite of forecasting,

which was designed to reduce uncertainty to the most likely outcome. As the

refinery story suggests, putting all your eggs in one basket, or forecast, is dangerous.

The next major step in scenario planning was the methodology developed at

Global Business Network (GNB), led by Jay Ogilvy and Peter Schwarz. Scenario

development in Shell was not a well-documented process. Scenarios were developed

by a small number in Group Planning, and individuals learned the approach

more or less by osmosis. GBN was the first to develop and publicize a structured

methodology to develop scenarios. Peter Schwarz’s 1991 book, The Art of the Long

View, outlined an approach to developing scenarios focused on identifying critical

uncertainties. Moreover, the process involved working through a series of steps in a

workshop setting. The central logic that scenarios were focused on identifying and

understanding uncertainties was crystallized by the methodology created by GBN.

The last major step in the evolution of scenario planning was connecting scenarios

to strategy. This is less well defined. The first major step in connecting scenarios

to decision-making involved two ideas developed by Kees van der Heijden.

One was the seven questions; the other was the management implications workshop.

The role of the seven questions was to elicit input from senior managers who did

not participate directly in developing the scenarios. The questions provided useful

information on management’s perspectives, created a direct link to management, and

built management support for the scenarios.

The other was the management implications workshop, first used with the 1989 Shell

scenarios, engaged management teams by asking the simple question: What are the

implications of the scenarios for your business? It evoked great conversation, embedded

the scenarios in the minds of senior managers, and created a mental mindset open to

new ideas and a willingness to act.

While this was a first step in creating strategic thinking, the process was not well

structured. In working first with Lee van Horn at Palomar Consulting and then

with Greg MacGillivray at Scenarios to Strategy, a structured process to link the

creative work of scenarios with the more focused work of strategy development

and implementation was developed. The process identifies the implications of the

scenarios, strategic thrusts, or focus areas, for the organization, goals, strategies, and

actions. The analysis linking the scenarios to strategy can vary depending on the level

of senior management involved, the objectives of the project, and the expected role

of the facilitators. Describing a process to link scenarios to strategy is a major aspect

of this work.

Strategic Management Model

Scenario planning is most effective as part of a strategic management process. Figure 1 outlines a simple but powerful strategic management model in which strategic scanning of the external environment provides a basis for strategy development, strategy implementation, and performance management. Over time, changes in the external environment and internal processes lead to feedback that may require adjustments in understanding the external world or internal implementation of the existing strategy.

Scenarios are a specific tool in the strategic scanning process. Scanning includes an analysis of the current external environment (social, technological, economic, environmental, and political factors), the current and emerging competitive environment (including actions of competitors and changes in regulation, as appropriate to the organization), as well as perspectives on the future. Altogether this may be referred to as the external environment or business environment.3 All planning requires perspective on the future, whether implicitly assumed or explicitly articulated. Scenarios specifically articulate a range of perspectives on how the future business environment could unfold.

The scenarios thus provide a context for developing and analyzing a range of potential strategies. The scenarios may stimulate thinking on a number of new strategies or a context for evaluating existing strategies. Scenarios provide the context for asking the question: If Strategy X is pursued, what are the risks and rewards if Scenario A occurs, or Scenario B occurs, or Scenario C occurs, et cetera? Repeat for Strategy Y, Z, et cetera. In this way, the value and robustness of each strategy is

analyzed in the face of the uncertainty of the future.

Following strategy development, the analysis should focus on a small number of strategies for implementation. Good strategy is often undermined by poor implementation. As a result, the implementation needs to be monitored and updated. Performance management involves monitoring both the implementation of the strategy and performance of the organization. A common tool for evaluating performance is the balanced scorecard, which can be adapted for both managing the strategy implementation and monitoring organization performance.

A key part of the model is the feedback loops to strategy. One learning loop involves changes in performance that require adjustments in implementation of the strategy. This is a management loop designed to adjust the implementation of strategy as conditions change. A second business loop provides feedback on changing external conditions. This feedback may alter the original scenario conditions and expectations or the original analysis in the development of the strategies. While the management loop is an adjustment to existing strategy, the business loop can challenge the overall strategy structure. The latter may require updated scenario thinking.

The focus of this book is on scenarios and strategy development leading to implementation and performance management. The scenario-planning approach emphasizes that scenarios are most effective and valuable as part of a strategic planning process in which scenarios are an initial phase in a larger strategic learning conversation. This process is critical to sound strategic planning. Don Michael (1973) initially articulated the insight that planning is learning. Equally, all learning comes from conversation. Hence, the power of scenarios is their role in strategic conversation—a dominant theme throughout the book.

Figure 1—Strategic Management Model

Scenarios are a specific tool in the strategic scanning process. Scanning includes an analysis of the current external environment (social, technological, economic, environmental, and political factors), the current and emerging competitive environment (including actions of competitors and changes in regulation, as appropriate to the organization), as well as perspectives on the future. Altogether this may be referred to as the external environment or business environment.3 All planning requires perspective on the future, whether implicitly assumed or explicitly articulated. Scenarios specifically articulate a range of perspectives on how the future business environment could unfold.

The scenarios thus provide a context for developing and analyzing a range of potential strategies. The scenarios may stimulate thinking on a number of new strategies or a context for evaluating existing strategies. Scenarios provide the context for asking the question: If Strategy X is pursued, what are the risks and rewards if Scenario A occurs, or Scenario B occurs, or Scenario C occurs, et cetera? Repeat for Strategy Y, Z, et cetera. In this way, the value and robustness of each strategy is

analyzed in the face of the uncertainty of the future.

Following strategy development, the analysis should focus on a small number of strategies for implementation. Good strategy is often undermined by poor implementation. As a result, the implementation needs to be monitored and updated. Performance management involves monitoring both the implementation of the strategy and performance of the organization. A common tool for evaluating performance is the balanced scorecard, which can be adapted for both managing the strategy implementation and monitoring organization performance.

A key part of the model is the feedback loops to strategy. One learning loop involves changes in performance that require adjustments in implementation of the strategy. This is a management loop designed to adjust the implementation of strategy as conditions change. A second business loop provides feedback on changing external conditions. This feedback may alter the original scenario conditions and expectations or the original analysis in the development of the strategies. While the management loop is an adjustment to existing strategy, the business loop can challenge the overall strategy structure. The latter may require updated scenario thinking.

The focus of this book is on scenarios and strategy development leading to implementation and performance management. The scenario-planning approach emphasizes that scenarios are most effective and valuable as part of a strategic planning process in which scenarios are an initial phase in a larger strategic learning conversation. This process is critical to sound strategic planning. Don Michael (1973) initially articulated the insight that planning is learning. Equally, all learning comes from conversation. Hence, the power of scenarios is their role in strategic conversation—a dominant theme throughout the book.

Figure 1—Strategic Management Model

Learning from Lost Luggage

The process of developing scenarios has evolved. From my early experience with scenarios in Shell, the process was intuitive and top down. The early work of Pierre Wack and Ted Newland depended heavily on their individual insights and brilliance. The understanding of the value of scenarios in opening minds was understood. Well-funded research and the active exchange of ideas both within Group Planning and with leading thinkers outside the company generated quality work that enhanced respect for scenarios in Shell and externally. The process, however, remained more intuitive than systematic and dependent on the insights of a small

group of experts.

My first exposure to an alternative process came by chance during an extended trip to Latin America in 1990. We were visiting the major Shell companies in the region to present the recently developed global scenarios and engage the management teams in an active discussion of the implications of the scenarios for their countries and businesses. The trip was successful but an accidental hiccup in our travel plans occurred when travelling from Chile to Mexico. We had to pass through Miami. We arrived in Mexico City but our luggage and all our presentation and workshop materials remained circulating in Miami. With a full day committed, our hosts wondered if instead of the global scenarios we could develop scenarios of Mexico. We were totally unprepared. But we tried and blundered our way to creating scenarios for Mexico from scratch in a day. This experience firmly implanted the power of workshops in my mind. It opened a new perspective on how scenarios could be developed.

While I subsequently experimented with a workshop approach to developing scenarios, consultants at Global Business Network (GBN) were developing a systematic, workshop-based approach to scenario development. When I left Shell and connected with GBN in the mid 1990s I was exposed to this brilliant methodology. The key insight was that the essential idea in scenarios was the concept of uncertainty.

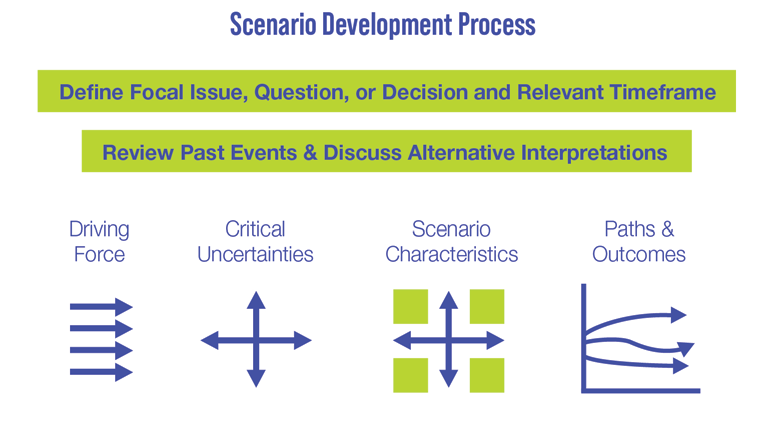

Consequently, the key step in developing scenarios is to identify the critical uncertainties that define the range of future outcomes. In effect, GBN codified the intuitive knowledge of scenarios into a step-by-step approach to developing scenarios. The purpose of Part 2 is to outline the five steps in a workshop-based approach to developing focused scenarios (Figure 6). The approach is based on the GBN model with modifications.

1. Creating Focus – The Focal Question

2. Identifying the Driving Forces

3. Developing Critical Uncertainties

4. Identifying Scenario Characteristics

5. Developing Scenario Paths and Outcomes

Figure 6—Process of Scenario Development

group of experts.

My first exposure to an alternative process came by chance during an extended trip to Latin America in 1990. We were visiting the major Shell companies in the region to present the recently developed global scenarios and engage the management teams in an active discussion of the implications of the scenarios for their countries and businesses. The trip was successful but an accidental hiccup in our travel plans occurred when travelling from Chile to Mexico. We had to pass through Miami. We arrived in Mexico City but our luggage and all our presentation and workshop materials remained circulating in Miami. With a full day committed, our hosts wondered if instead of the global scenarios we could develop scenarios of Mexico. We were totally unprepared. But we tried and blundered our way to creating scenarios for Mexico from scratch in a day. This experience firmly implanted the power of workshops in my mind. It opened a new perspective on how scenarios could be developed.

While I subsequently experimented with a workshop approach to developing scenarios, consultants at Global Business Network (GBN) were developing a systematic, workshop-based approach to scenario development. When I left Shell and connected with GBN in the mid 1990s I was exposed to this brilliant methodology. The key insight was that the essential idea in scenarios was the concept of uncertainty.

Consequently, the key step in developing scenarios is to identify the critical uncertainties that define the range of future outcomes. In effect, GBN codified the intuitive knowledge of scenarios into a step-by-step approach to developing scenarios. The purpose of Part 2 is to outline the five steps in a workshop-based approach to developing focused scenarios (Figure 6). The approach is based on the GBN model with modifications.

1. Creating Focus – The Focal Question

2. Identifying the Driving Forces

3. Developing Critical Uncertainties

4. Identifying Scenario Characteristics

5. Developing Scenario Paths and Outcomes

Figure 6—Process of Scenario Development

What Went Wrong? Coal Scenarios 2005—Insights from he Past

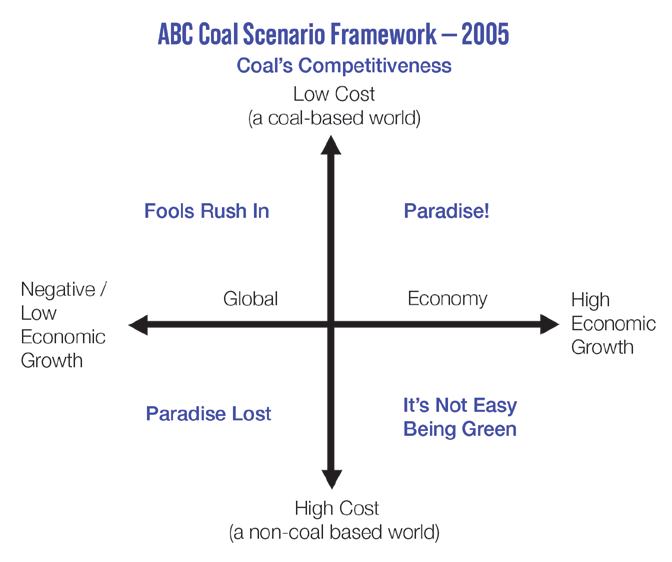

The scenarios framework shown in Figure 25 is based on two critical uncertainties. One focuses on the potential for economic growth that drives the demand for electricity. Second is the competitiveness of coal versus other fuels in the market for power production. The outlook was rosy. Projections of power demand were bullish. Coal was cost competitive with other fuels. Nuclear power was hampered by construction cost overruns and safety concerns. Natural gas was extremely expensive, and projections emphasized future gas shortages. Renewables were only viable with large subsidies and were not dispatchable (i.e., they are produced intermittently when the wind blows and the sun shines, requiring coal or gas backup capacity). Dirty but cheap seemed like a reasonable trade-off.

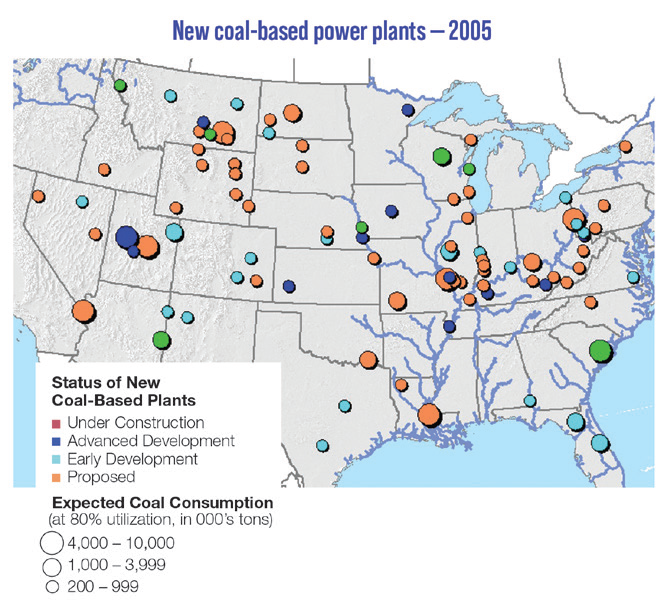

Coupled with this analysis was the investment going into coal. Figure 26 shows the coal-fired power plants under construction, advanced development, early development, or proposed in 2005.

Figure 25—Coal Scenario Framework

Coupled with this analysis was the investment going into coal. Figure 26 shows the coal-fired power plants under construction, advanced development, early development, or proposed in 2005.

Figure 25—Coal Scenario Framework

The scenarios challenged that bright future by recognizing the potential impact of environmental concerns. Paradise! was driven by technology and economy. Strong growth would drive demand and combined cycle technology would raise efficiency and lower CO2 emissions. Fools Rush In, was characterized by a weak economy and stagnant demand. Security and cost concerns gave coal a strong competitive edge, sustaining demand. Paradise Lost explored a future in which weak economic growth undermined power demand and politics determined regulation.

Conservation by force meant high carbon penalties with a shift to gas. It’s Not Easy Being Green focused on rising environmental concerns during a period of strong economic growth. High energy prices and government initiatives would affect demand for dirty coal. In both Paradise Lost and It’s Not Easy Being Green, the main mechanism was seen as a CO2 trading system. In the latter, however, there would be a greater penetration of renewables supported by direct government subsidies. In the analysis, the prospects for coal were reinforced by considering the cost per tonne of CO2 emissions. Even with high penalties of $50 per tonne (in 2005), coal remained competitive with natural gas, which was projected to exceed $10 per thousand cubic feet for the foreseeable future.

Figure 26—Proposed Coal-Based Power Plants

Conservation by force meant high carbon penalties with a shift to gas. It’s Not Easy Being Green focused on rising environmental concerns during a period of strong economic growth. High energy prices and government initiatives would affect demand for dirty coal. In both Paradise Lost and It’s Not Easy Being Green, the main mechanism was seen as a CO2 trading system. In the latter, however, there would be a greater penetration of renewables supported by direct government subsidies. In the analysis, the prospects for coal were reinforced by considering the cost per tonne of CO2 emissions. Even with high penalties of $50 per tonne (in 2005), coal remained competitive with natural gas, which was projected to exceed $10 per thousand cubic feet for the foreseeable future.

Figure 26—Proposed Coal-Based Power Plants

What happened? Two unexpected events overtook the thinking in the scenarios. First, the scenarios understood the impact of carbon penalties would be a cost of doing business. Even high penalties meant that coal could remain competitive. Coal producers would simply pay to emit CO2. This view changed. Financial investors became concerned that the risks from climate change policies could be very high. More important, they could not quantify the risks. Wall Street pulled the plug on new coal investments and none of the almost 200 power plants planned in the US could attract funding.

Second, assumptions about natural gas were, literally, fractured. With hydraulic fracturing, production of natural gas surged and prices fell. Independent of carbon penalties, the cost of electricity production from natural gas fell below that of coal. Coal lost its competitive edge. The market, not regulation, undermined the coal industry in the US. The purpose of scenarios is to expose these events, to think the unthinkable.

Why did we not see these potential events in 2005? To some degree we were successful in raising the risks associated with rising climate change concerns and potential regulatory penalties. What we failed to identify was how those environmental risks would play out with the abrupt collapse of financing. The threat turned out not to be just a straightforward cost of doing business. Nor did we—the coal company executives and us as facilitators—foresee the radical change in the natural gas supply.

Economics might have given us a clue. High gas prices should stimulate supply, but we relied on technical expertise which said the gas did not exist. This is a cautionary tale. The process worked, but we were not radical enough in our thinking. Use scenarios to embrace the unthinkable and think the unbelievable.

Second, assumptions about natural gas were, literally, fractured. With hydraulic fracturing, production of natural gas surged and prices fell. Independent of carbon penalties, the cost of electricity production from natural gas fell below that of coal. Coal lost its competitive edge. The market, not regulation, undermined the coal industry in the US. The purpose of scenarios is to expose these events, to think the unthinkable.

Why did we not see these potential events in 2005? To some degree we were successful in raising the risks associated with rising climate change concerns and potential regulatory penalties. What we failed to identify was how those environmental risks would play out with the abrupt collapse of financing. The threat turned out not to be just a straightforward cost of doing business. Nor did we—the coal company executives and us as facilitators—foresee the radical change in the natural gas supply.

Economics might have given us a clue. High gas prices should stimulate supply, but we relied on technical expertise which said the gas did not exist. This is a cautionary tale. The process worked, but we were not radical enough in our thinking. Use scenarios to embrace the unthinkable and think the unbelievable.